The driver is a block whose role is to interact with the DUT. The driver pulls transactions from the sequencer and sends them repetitively to the signal-level interface. This interaction will be observed and evaluated by another block, the monitor, and as a result, the driver’s functionality should only be limited to send the necessary data to the DUT.

In order to interact with our adder, the driver will execute the following operations: control the en_i signal, send the transactions pulled from the sequencer to the DUT inputs and wait for the adder to finish the operation.

So, we are going to follow these steps:

- Derive the driver class from the uvm_driver base class

- Connect the driver to the signal interface

- Get the item data from the sequencer, drive it to the interface and wait for the DUT execution

- Add UVM macros

In Code 5.1 you can find the base code pattern which is going to be used in our driver.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 | class simpleadder_driver extends uvm_driver#(simpleadder_transaction); `uvm_component_utils(simpleadder_driver) //Interface declaration protected virtual simpleadder_if vif; function new(string name, uvm_component parent); super.new(name, parent); endfunction: new function void build_phase(uvm_phase phase); super.build_phase(phase); void'(uvm_resource_db#(virtual simpleadder_if)::read_by_name(.scope("ifs"), .name("simpleadder_if"), .val(vif))); endfunction: build_phase task run_phase(uvm_phase phase); //Our code here endtask: run_phase endclass: simpleadder_driver |

Code 5.1 – Driver component – simpleadder_driver.sv

The code might look complex already but what it’s represented it’s the usual code patterns from UVM. We are going to focus mainly on the run_phase() task which is where the behaviour of the driver will be stated. But before that, a simple explanation of the existing lines will be given:

- Line 1 derives a class named simpleadder_driver from the UVM class uvm_driver. The #(simpleadder_transaction) is a SystemVerilog parameter and it represents the data type that it will be retrieved from the sequencer.

- Line 2 refers to the UVM utilities macro explained on chapter 2.

- Lines 7 to 9 are the class constructor.

- Line 11 starts the build phase of the class, this phase is executed before the run phase.

- Line 13 gets the interface from the factory database. This is the same interface we instantiated earlier in the top block.

- Line 16 is the run phase, where the code of the driver will be executed.

Now that the driver class was explained, you might be wondering: “What exactly should I write in the run phase?”

Consulting the state machine from the chapter 1, we can see that the DUT waits for the signal en_i to be triggered before listening to the ina and inb inputs, so we need to emulate the states 0 and 1. Although we don’t intend to sample the output of the DUT with the driver, we still need to respect it, which means, before we send another sequence, we need to wait for the DUT to output the result.

To sum up, in the run phase the following actions must be taken into account:

- Get a sequence item

- Control the en_i signal

- Drive the sequence item to the bus

- Wait a few cycles for a possible DUT response and tell the sequencer to send the next sequence item

The driver will end its operation the moment the sequencer stops sending transactions. This is done automatically by the UVM API, so the designer doesn’t need to to worry with this kind of details.

In order to write the driver, it’s easier to implement the code directly as a normal testbench and observe its behaviour through waveforms. As a result, in the next subchapter (chapter 5.1), the driver will first be implemented as a normal testbench and then we will reuse the code to implement the run phase (chapter 5.2).

Chapter 5.1 – Creating the driver as a normal testbench

For our normal testbench we will use regular Verilog code. We will need two things: generate the clock and idesginate an end for the simulation. A simulation of 30 clock cycles was defined for this testbench.

The code is represented in Code 5.2.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | //Generates clock initial begin #20; forever #20 clk = ! clk; end //Stops testbench after 30 clock cyles always@(posedge clk) begin counter_finish = counter_finish + 1; if(counter_finish == 30) $finish; end |

Code 5.2 – Clock generation for the normal testbench

The behaviour of the driver follows in Code 5.3.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 | //Driver always@(posedge clk) begin //State 0: Drives the signal en_o if(counter_drv==0) begin en_i = 1'b1; state_drv = 1; end if(counter_drv==1) begin en_i = 1'b0; end case(state_drv) //State 1: Transmits the two inputs ina and inb 1: begin ina = tx_ina[1]; inb = tx_inb[1]; tx_ina = tx_ina << 1; tx_inb = tx_inb << 1; counter_drv = counter_drv + 1; if(counter_drv==2) state_drv = 2; end //State 2: Waits for the DUT to respond 2: begin ina = 1'b0; inb = 1'b0; counter_drv = counter_drv + 1; //After the supposed response, the TB starts over if(counter_drv==6) begin counter_drv = 0; state_drv = 0; //Restores the values of ina and inb //to send again to the DUT tx_ina <= 2'b11; tx_inb = 2'b10; end end endcase end |

Code 5.3 – Part of the driver

For this testbench, we are sending the values of tx_ina and tx_inb to the DUT, they are defined in the beginning of the testbench (you can see the complete code attached to this guide).

We are sending the same value multiple times to see how the driver behaves by sending consecutive transactions.

After the execution of the Makefile, a file named simpleadder.dump will be created by VCS. To see the waveforms of the simulation, we just need to open it with DVE.

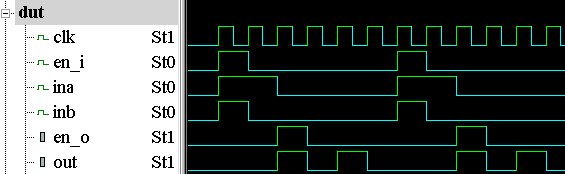

The waveform for the driver is represented on Figure 5.1.

It’s possible to see that the driver is working as expected: it drives the signal en_i on and off as well the DUT inputs ina and inb and it waits for a response of the DUT before sending the transaction again.

Chapter 5.2 – Implementing the UVM driver

After we have verified that our driver behaves as expected, we are ready to move the code into the run phase as seen in Code 5.4.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 | virtual task drive(); simpleadder_transaction sa_tx; integer counter = 0, state = 0; vif.sig_ina = 0'b0; vif.sig_inb = 0'b0; vif.sig_en_i = 1'b0; forever begin if(counter==0) begin //Gets a transaction from the sequencer and //stores it in the variable 'sa_tx' seq_item_port.get_next_item(sa_tx); end @(posedge vif.sig_clock) begin if(counter==0) begin vif.sig_en_i = 1'b1; state = 1; end if(counter==1) begin vif.sig_en_i = 1'b0; end case(state) 1: begin vif.sig_ina = sa_tx.ina[1]; vif.sig_inb = sa_tx.inb[1]; sa_tx.ina = sa_tx.ina << 1; sa_tx.inb = sa_tx.inb << 1; counter = counter + 1; if(counter==2) state = 2; end 2: begin vif.sig_ina = 1'b0; vif.sig_inb = 1'b0; counter = counter + 1; if(counter==6) begin counter = 0; state = 0; //Informs the sequencer that the //current operation with //the transaction was finished seq_item_port.item_done(); end end endcase end end endtask: drive |

Code 5.4 – Task for the run_phase()

The ports of the DUT are acessed through the virtual interface with vif.<signal> as can be seen in lines 4 to 6.

Lines 12 and 50 use a special variable from UVM, the seq_item_port to communicate with the sequencer. The driver calls the method get_next_item() to get a new transaction and once the operation is finished with the current transaction, it calls the method item_done(). If the driver calls get_next_item() but the sequencer doesn’t have any transactions left to transmit, the current task returns.

This variable is actually a UVM port and it connects to the export from the sequencer named seq_item_export. The connection is made by an upper class, in our case, the agent. Ports and exports are going to be further explained in chapter 6.0.1.

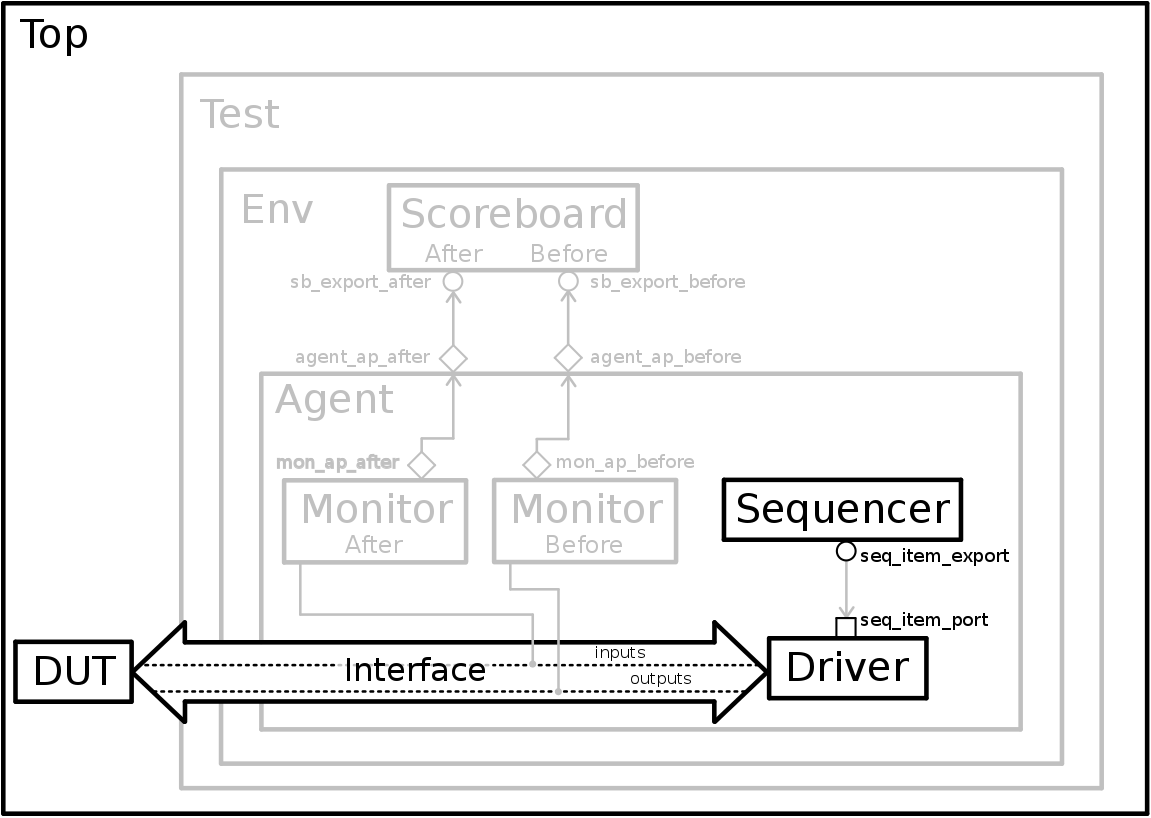

This concludes our driver, the full code for the driver can be found in the file simpleadder_driver.sv. In Figure 5.2, the state of the verification environment with the driver can be seen.

Figure 5.2 – State of the verification environment with the driver

Figure 5.2 – State of the verification environment with the driver

The source of the driver can be accessed here: